By N. H. Gill

Nov. 24, 2018

Indigenous elites stood at the intersection of political subjugation and cultural survival in Spanish and Portuguese America. Over more than three centuries they acted as intermediaries between their communities and outsiders, as defenders before the law, and even as collaborators with local power groups in the exploitation of their own people. As such, they wielded enormous power that Europeans struggled to control throughout the colonial period. Yet over time, the Iberian monarchs were able to exact some form of cooperation and slowly pressure renegades out of power. In other cases, elites were coopted to such a degree that they lost legitimacy in their communities and became ineffective leaders. But ultimately, these outcomes served neither Europeans nor Native Americans, a predicament that sheds light on the difficult role occupied by this ethnic elite. Because physically conquering whole continents was beyond the capability of Spain and Portugal, both colonial powers relied on Indigenous elites to project European hegemony into Indigenous societies, especially in areas far from the vice regal centers of power. This resulted in a slow but enduring form of subjugation. Also important to the creation of this soft power was the Catholic Church, whose indoctrination, control, and education of generations of Amerindians proved a formidable tool of cultural conquest. Still, the power and persistence of Indigenous societies at the end of the colonial period stands as a testament to the partial successes of the Indigenous elite in helping their communities adapt to historic change in colonial Latin America.

In the early conquest period, Spanish and Portuguese colonists encountered various forms of social hierarchies in different parts of the region, but two broad categories of elites emerged as the most relevant: the religious and political. Yet religious priests and prophets seemed to provoke Europeans in deeper ways, leading to a pattern of violent repression. In contrast, colonists sought to co-opt political leaders represented by kurakas, as they were known in the Andes, or caciques, a Taíno term used in other regions of Spanish America. Conditions in Brazil present variations that are not easily captured by patterns seen in the Spanish Americas. In the former, whether from epidemics or less sedentary forms of traditional organization, Indigenous populations were lower and lived in less densely-populated groups, which complicated Portugal’s efforts to organize labor systems for the agro-export economy it was trying to build on the Atlantic coast. Given these regional conditions, mixed European-Americans, known as mamelucos, played a larger role there, acting as intermediaries between Indigenous communities and colonial settlers in Brazil.

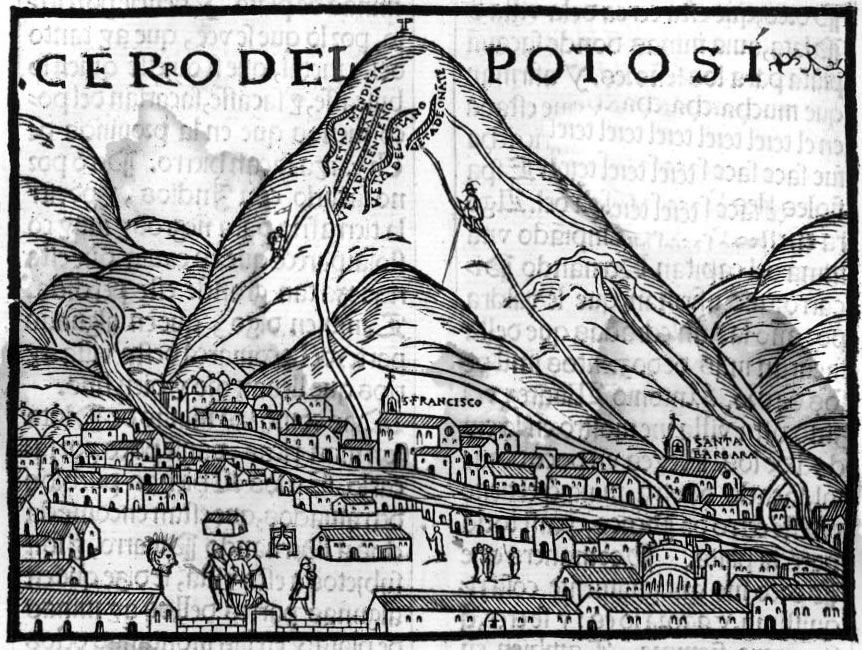

In the Andes, Steve Stern highlighted the interplay between religious and political resistance in the first decades after the Spanish arrival. Looking at the relatively core area of Huamanga along the important Lima-Cuzco-Potosí highway, Stern argued that much of traditional Andean political economy remained in place after conquest with Spanish overlords replacing Incan authorities, but not fundamentally ending the basic ayllu-based economy. Up until approximately 1570, Spanish officials used pre-Colombian social organizations to administer control in the Andes. Under that system, kurakas were expected to defend their peoples’ interests, distribute lands, adjudicate internal conflicts, oversee the circulation and storage of goods, and organize and maintain religious rites. This began to change as encomenderos increasingly plied kurakas with rewards, land, and concessions, giving them early advantages in the nascent commercial economy.

Under these conditions, the indigenous elite were the first to become Hispanicized, allowing Spain to gain a powerful foothold in the Andean world. However, as Stern observes, kurakas walked a fine line between the use and abuse of their kin. If unable to protect their people they could lose their communities’ respect. On the other hand, by too often refusing Spanish demands, they could be punished or replaced. Ultimately, Stern says, kurakas failed to protect their communities, as seen in the rise of the Taki Onqoy movement. This religious resistance movement challenging all things Spanish was pushed by middle and lower-ranking segments of Indigenous society, not the elite. Forced to choose between abandoning the source of their new privilege or supporting a movement against a powerful colonial force, Stern says many kurakas sided with the Spanish.

The many crises of this period spurred support for reform, which in the Andes came in the late sixteenth century from a series of viceroys, most notably Francisco de Toldeo. As new mercury-amalgamation techniques revolutionized silver production, a new phase of colonization began that required more workers and further undermined traditional social ties between Indigenous communities and the elite. The development of the República de Indios and República de Espanoles as separate legal spheres added new administrative layers, including the so-called alcaldes mayores and corregidores de Indios, which drove the creation of new “power groups.” These groups were a mixture of Spanish, mestizo, Indigenous, and other local notables, who allied to exploit local communities for commercial profit. This shows change in the role of Indigenous elite, from the post-Conquest period of Spanish colonization, when kurakas more often worked to protect their kinfolk, to later times when kurakas and other Indigenous elite began to achieve some commercial success and depended more on the Spanish for their future.

Karen Spalding’s generative work on the colonial history of Huarochirí complements Stern’s assessment of the changing role of the Indigenous elites in the early years of Andean conquest. Looking at Huarochirí, a rural region that was close enough to Lima to benefit from its commerce, Spalding agrees that Spanish conquerors’ initial strategy was to maintain Incan hierarchies, replacing only the regional Incan governors with a new class of Spanish encomenderos. Comparing kurakas to a sharp blade slicing through the body of traditional Andean society, Spalding argues that the Indigenous elite became power brokers between their Indigenous communities and the Spanish state. They were most successful when they were able to keep tribute flowing while simultaneously preventing the Europeans from interfering with the internal structure of their communities.

Rural areas like Huarochirí also benefitted from de-centralized colonial control, which allowed them to maintain core cltural lifeways while integrating into the political and religious life of Spanish society. Spalding’s long research horizon allows her to connect early revolts, such as the Taki Onqoy movement, with the later Túpac Amaru II movement, complicating Stern’s claim that by 1640 Andeans were a defeated people. Still, both concur that the Andean elite initially accepted encomendero rule as a way to preserve their traditional roles as community leaders. For Spalding, the Toledan reforms that formalized the position of kurakas as an arm of the colonial state were significant because they made local elites dependent on the Spanish Crown as opposed to their communities.

Indigenous elites also served as cultural mediators, negotiating the real implementation of colonialism, softening the blow when possible, but also extracting the precious economic surplus from their own communities. While many clearly exploited and abused their communities, others shielded their subjects from colonial predation as best they could.

The Spanish colonization of the Maya world provides a revealing contrast to the transformation of areas like Huarochiri in Peru. In the earliest years of Mesoamerican colonization, the Catholic Church was essential to the conquest. Because of a challenging environment, whose harsh climate and lack of precious-metal deposits made it economically unattractive in the early years of conquest, the Spanish relied more on religious indoctrination than military force to project their power in this region. For this reason, religious education and literacy were key to colonial efforts there. Inga Clendinnen’s 1987 monograph, Ambivalent Conquests, emphasizes this situation in the Yucatan, exploring how religious and political elites, known as batabob, navigated the arrival of a particularly violent wave of conquisitadores and Franciscan priests.

Photo by Matthew Essman on Unsplash.

Understanding religious practices is key to appreciating the role of the elite in the Mayan world. Clendinnen helpfully explains the cyclical nature of Mayan religion and importance of how to read and record past events, focusing on the role of literacy in chronicling the past and exploring the future. The author says that relatively quickly Mayan priests were hunted down and usually killed, whereas some political leaders were tapped to fill new leadership positions. Like the Andes, Spanish settlers maintained Indigenous hierarchies, relying on local leadership structures to carry out what Clendinnen describes as a plunder economy. Also similar to the Andes, the arrival of Franciscan missionaries seems to played a significant role in Mayan society in the first century of colonization. Like in Cuzco, schools for the sons of elites were created as a means of evangelizing the wider Indigenous population with the boys as “mediators” between Spanish and Indigenous communities. Over time, especially after the 1562 inquisition, Clendinnen says that the conquest eroded many traditions, but left local leadership structures and economic bases relatively unchanged until at least the seventeenth century. Along the way, Indigenous lords made a “calculated accommodation” with Spanish rule.

Indigenous elites were also important in Brazil, but their participation in colonial life took a different form. Alida Metcalf’s work on so-called “go-betweens” in colonial Brazil stresses the role of third parties, who were critical in the ultimate success of Portugal’s venture in the Americas. Go-betweens acted as multicultural brokers between Europeans and Native Americans, holding a somewhat analogous position to Andean kurakas and the Mayan batabob in the mediation of conquest. Metcalf’s theoretical development of these go-between includes physical, transactional, and representational actors who helped shape relations between Europeans and Brazilian Indigenous communities. While conceptually useful, this framework seems too broad, especially within the category of representational go-betweens.

Mamelucos and native prophets also played key roles in the development of the early colonial economy, which in Brazil centered around slaves, sugar, and brazilwood by the late sixteenth century. According to Metcalf, mamelucos were essential in wresting the continent away from its native inhabitants. In the earliest years of colonization, mamelucos often worked in cooperation with Indigenous chiefs at the expense of Portuguese interests because their survival in the frontier sertão depended on their ability to work with and dominate Indigenous groups. Over time, this relationship made them the most successful in convincing Indigenous groups to “descend” to Portuguese settlements and submit to Portuguese authority. As the power of the Portuguese state increased over time, mameluco go-betweens increasingly favored the interests Portuguese colonist over Indigenous villagers.

Looking beyond Metcalf’s work, it appears economic differences may have played a significant role in the different outcomes between Brazil and the Andes. In the early colonial period, the Portuguese were interested in the extraction of brazilwood and sugar, both European-controlled markets, whereas in the Andes the Spanish continued to rely on native economies to supply their mining economy. Where elite intermediaries such as mamelucos emerged from Brazil’s colonization process itself, Andean leadership structures were carried over from the Incan state.

Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on Unsplash.

In conclusion, Indigenous elites across the Americas changed over time, from early defenders of their native communities, to complex intermediaries responsible for ensuring Indigenous compliance with colonial rule, to increasingly-alienated exploiters. By the end of the colonial period many in this elite class had adopted European customs and lifeways and played an active role in the exercise of colonial power. Yet, this gradual shift away from their communities eventually undermined their effectiveness, for both their subjects and Spanish administrators, leading to their ultimate downfall as a colonial class.

Second, distance between the so-called core and periphery played a major role in the development of the Indigenous elite in the colonial period. In areas like Mesoamerica, Mayan leadership structures and modes of production changed less, allowing native leaders to remain vital to local societies and to choose, within limits, which features of colonial rule benefitted them most. In more central areas like Cuzco, intermarriage, political cooptation, and cultural assimilation worked much faster to undermine traditional relationships between villagers and their native rulers.

Third, variations in local economic systems probably played a significant role in how these elite classes developed over time. In the case of Brazil, where lower population densities required the creation of new labor systems, the local elites who emerged from these processes were often racially-mixed individuals. Their ability to mediate between European and Indigenous cultures and worldviews made them essential in convincing local groups to descend into the Portuguese sphere of power.

Finally, in all of the areas considered here the physical enormity of the land, the differences between local cultures, and the relatively few European colonists who settled there meant that colonial projects could not be carried out by military conquest alone. The Iberian monarch needed the active participation of local leaders to project hegemony outside of colonial centers of power. In this respect, the Catholic Church played an influential role in carrying Spanish culture into the periphery and breaking down cultural resistance to colonial rule. By educating Indigenous children and requiring Indigenous leadership to accept Christianity, at least on the surface, European colonists slowly brought the Americas under their control. Yet instead of vilifying this elite, the challenge of colonial historians is to understand the contexts these assuredly conflicted intermediaries lived in as they tried to navigate their peoples’ subjugation and survival.

Cover photograph: Complejo arqueológico, Pisac, Peru, by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos.

Works cited:

Clendinnen, Inga. Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatan, 1517-1570. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Garrett, David T. Shadows of Empire: The Indian Nobility of Cusco, 1750-1825. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Metcalf, Alida C. Go-Betweens and the Colonization of Brazil, 1500-1600. 1st ed. University of Texas Press, 2005.

Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí, an Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford University Press, 1984.

Stern, Steve J. Peru’s Indian Peoples and the Challenge of Spanish Conquest: Huamanga to 1640. University of Wisconsin Press, 1982.

Discover more from Southern Affairs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.